Nazi Lawyers: How the Nazis Co-opted the German Legal Profession and Codified Their Reign of Terror

“Roland Freisler was in no way a demon rising from hell; rather, he emerged from the midst of the German people. He was a merciless representative of a merciless justice, a consistent accomplice of a murderous system, a showcase murderer in a robe—and the Germans made his deeds, his impact, his career possible.”

Helmut Ortner, Der Hinrichter: Roland Freisler—Mörder im Dienste Hitlers

Examining Nazi laws and lawyers may seem like a futile exercise in contradiction. How could a tyrannical regime, characterized by arbitrary rule, which used merciless violence to enforce a system of terror have laws? Nevertheless, lawyers played a key role in codifying Nazi tyranny and terror. In 1933 Hitler and the Nazis rose to power and began a system of gleichschaltung, or co-ordination, in which all of German life was brought under Nazi party control. The legal profession was no exception.

Fundamentally the legal profession is one which prides itself on justice, fairness, and equality. Yet in Germany from 1933 to 1945 the Nazis were able to successfully co-opt the legal profession. The Nazis relied on their lawyers to write laws which promoted Nazi racial policies. Nazi judges participated in show trials in courts steeped in. In doing so German lawyers and jurists disabused themselves of notions of “justice,” “fairness,” and “equality” in favor of laws which were persecutory, anti-semitic, and wholly unjust. The Nazis were able to successful co-opt the legal profession because they took advantage of wage stagnation and underemployment among lawyers. The Nazis capitalized on this by blaming Jewish lawyers, and re-worked their victimhood rhetoric to apply to German lawyers. The Nazis were also adept at excluding those who would not acquiesce to Nazi rule form the professions. The lawyers who remained in their government posts often felt they were moderating forces, who steadied the German ship of state from more radical Nazi party leaders tried to disrupt it with extreme policies.

Upon seizing control of German government, the Nazis moved quickly to establish their legislative and judicial authority. In 1933 the “Law to Safeguard the Unity of Party and State” was codified. It ushered in a period of Nazi legislative supremacy. It also legally combined the Nazi party with the German State. However, the law was vague in its provisions, and the portions of the law which dealt with regulation of party and state rule were unclear (GHDI). This law was the first step of gleichschaltung. Most German lawyers joined the Bund NS Deutscher Juristen, a professional organization for lawyers.

During the economic downturn of Weimar Germany many of German lawyers found themselves under employed and without clients. Due to constrained budgets those who were clients withdrew their suits, those who would have been clients opted not to solicit the services of an attorney. Additionally, many government sector employees had their salaries cut. While lawyers did not suffer economically as bad as their blue collar counterparts, they did however, lose professional prestige. The economic struggles of German lawyers were compounded by a widely held German “professionalism complex” (Jarausch, 107, 109-110). German culture placed great prominence upon the professions. Consequently, Germans sought out professional careers, which created an overly saturated profession. Prior to the Nazi seizure of power the legal profession was in “crisis” according to some commentators (Jarausch, 110).

During the boycott Germans were instructed not to solicit the services of Jewish lawyers.

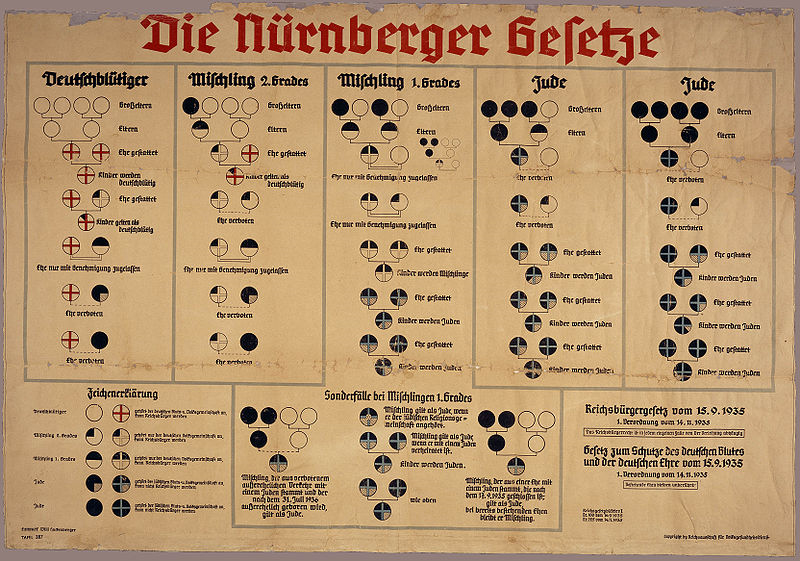

As the Nazis tightened their control over Germany enacted various anti-Semitic laws some of which targeted Jewish professionals. Jewish lawyers bore the brunt of these targets. They were often targeted for violent attack, and during the infamous two day boycott Germans were instructed not to solicit Jewish attorneys. During gleichschaltung the Nazis excluded Jewish lawyers from practicing. In 1933 the Nazis enacted the “Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service” and the “Law Regarding Admission to the Bar” (GHDI). These laws specifically targeted Jewish civil servants and attorneys the law stated that, “Officials who are of non-Aryan descent are to be retired.” The laws also targeted the political adversaries of the Nazis, “unfit are all civil servants who belong to the Communist Party or Communist auxiliary or supplementary organizations. They are, therefore, to be discharged.” The Bar laws were also changed, unde these regulations Jewish people were barred from being called to the bar ( Roderick Stackelberg, Sally A. Winkle, 3.12a-b). When a Jewish person’s name was removed from the bar, they would receive a short letter informing them that their name had been removed from the list of people authorized to appear before their local court and the nearest district court. Further, the Nazi banned Jewish people from severing as lay judges or jury members (Gross, 92.)

Name sign of the attorney Werner Liebenthal, who was disbarred in 1933. Source: Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Name sign of the attorney Werner Liebenthal, who was disbarred in 1933. Source: Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The aforementioned laws benefitted both Aryan German lawyers, and Nazi politicians. Many German lawyers blamed Jewish lawyers for the downturn in attorney employment. Therefore, by eliminating a swath of the profession competition among lawyers was reduced. By benefiting German lawyers, the Nazis shored up support. In general many German lawyers welcomed Nazi rule with “restrained enthusiasm” (Jarausch). Support for the Nazis grew among German lawyers grew as Nazi policies benefitted the profession. Additionally, by eliminating any political opposition from the civil service the Nazis were able to install those who supported Nazi ideology. This was a key stage in the co-opting of the profession.

The People’s Court in session. The Court conducted thousands of show trials, and sentenced thousands of people to their death.

Nazi lawyers were uniquely complicit in formulating the Nazi system of terror. Many trained bureaucrats were trained lawyers who used their legal training to work within existing legal frameworks. Other civil service members knew what could done discreetly and without arousing too much public pushback. Additionally, the lawyers of the upper echelons of the “traditional” civil service were better educated and experienced than their counterparts in the newly established party and SS agencies. These experienced civil servants employed “pragmatism” which made them “appear to lack ideological zeal and to be less radical” (Jasch, 38). This brand of seeming self restraint gave civil servants the ability to view themselves as moderating forces, who saved Germany for more radical forces within the government (Koonz,108-9). This is not to say that civil servants were not supporters of the Nazi regime, indeed the Nazis enjoyed a high degree of buy-in from bureaucrats (Koonz, 169). Due to the high levels of competition for power within the Nazi State, the Nazi bureaucrats experienced a phenomenon known as “cumulative radicalization,” which created a “murderous dynamic that eventually culminated in genocide” (Jasch 37).

“Cumulative radicalization,” created a “murderous dynamic that eventually culminated in genocide.”

The Nazis helped ferment buy-in of the legal field by fundamentally redefining who lawyers represented. Attorneys became “an organ of the administration of justice [Rechtspflege]” which made it “his professional task to represent, in the interest of his client, what he considers true and right in a given case.” The Nazis shifted who the client was, from one person, to the entire German volk. In doing so the Nazis replaced legal equality with notions of racial hierarchy, and instituted their own sense of justice which prioritized the Aryan volk over all others. (Jarausch, 114). Thus defending a person accused of crimes against the volk became a dangerous endeavor, ensuring that political and racial opponents were doomed to conviction. (Jarausch, 129).

Throughout the Nazi period a dual state emerged. In 1941 Ernst Fraenkel, a Jewish refugee lawyer and legal scholar, published a widely read and influential examination of Nazi rule. In his bookThe Dual State Fraenkel posited an argument which held that in Nazi Germany both a traditional legal system persisted (though it was thoroughly Nazified), yet at the same time the Nazis constructed an extra-legal system of terror. Fraenkel proscribed the term “normative state” for the traditional legal order, which included the codes of German law, Ministry of Justice, and the courts. All of these were certainly infused with and affected by Nazi policies and personnel, however, they retained their traditional connections to justice and fairness.

The lawlessness of the Nazi regime was actively supported by the People’s Court, a murderous organization given vast powers, cloaked under the auspices of a serious judicial body. The People’s Court was given broad just dictional powers to hear cases of treason. The death penalty was reinstated by the Nazis, the People’s Court took liberal advantage of this new law (Geerling, et. al.,215). Additionally, the rulings of the People’s Court were final and not subject to appeals. The Nazis also used the onset of the war to justify expanding the powers of the court. (Geerling, 216-7).

The Judge President of the People’s Court Dr. Freisler

Roland Freisler was the Judge President of the People’s Court from 1942-1945, under his leadership the court conducted many show trials, and acted a juridical tool of the Nazi regime. Under Freisler the court abandoned “all pretense of judicial impartiality, cast off any veneer of judicial dignity.” Rather, the People’s Court became solely focused on implementing Nazi terror. The court took note of the religious affiliations of defendants and cited discrete sections of the penal code. The court handed down countless brutal sentences for seemingly minor offenses. The decisions of the People’s Court were “little more than vigilante justice executed under the cover of a red robe” (Rachlin, 63-5). The People’s Court played a key role in implanting the Nazi’s “legislative program,” the rulings they handed down sent many Jewish people to concentration camps. Implicit in the act of using show trials is “the use of law as a means of persecution that is not purely instrumental” tool of justice (Rundle, 67). To further underscore the connections between party, state government, and the court, Freisler attended the Wannsee Conference (GHDI).

The People’s Court were “little more than vigilante justice executed under the cover of a red robe”

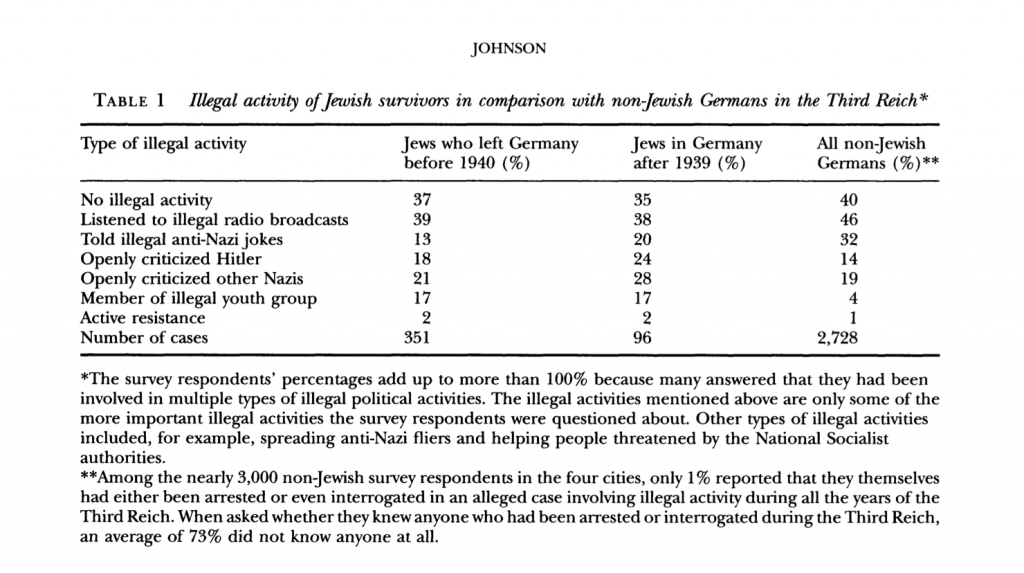

During the Nazi period sentence disparity was stark, ones religious identity, ethnicity, gender, and socio economic standing often mattered more than the crime one stood accused of. Throughout the Nazi period the Gestapo and other police services cultivated an image of being omnipresent, omnipotent, omnipotent” (Mallmann and Gerhard). However, the Gestapo was far less concerned with German crimes, rather, they devoted their resources to taking down, and prosecuting Jewish and Communist crimes. Thus the Nazis largely accepted a relatively high level of criminality among its own citizenry. It often gave its own citizens far more linens sentences than those given to Jewish individuals who were often convicted of far less. In Nazi Germany “what mattered most in Nazi jurisprudence was not what the crime was, but who committed the crime” (Johnson, 601).

The Nazis co-opted the legal profession in Germany and used it to codify racial hierarchy and Nazi brutality. The Nazis took advantage of the economic downturn to appeal to German attorneys. Nazi lawyers were active in formulating the most pernicious of Nazi laws, they used their legal training and bureaucratic expertise to formulate laws in a sterile and stale manner. Nazi judges on the People’s Court were active perpetrators, they put party above love, and sent thousands of people to their deaths. The Nazi period is fundamentally a period of seeming lawlessness, however, the Nazis had laws and operated within them. Nazi lawyers were guilty of perpetrating Nazi terror by codifying that very terror into German jurisprudence.

By: Thomas Duncan, Department of History, Loyola Marymount University, class of 2019.

Further Reading

Mallmann, Klaus-Michael and Gerhard Paul. “Omniscient, Omnipotent, Omnipresent? Gestapo, Society, and Resistance.” In Nazism and German Society, 1933-1945, edited by David F. Crew, 166-196. London/New York: Routledge, 2001.

“Roland Freisler and the Volksgerichtshof: The Court as an Instrument of Terror.” In The Law in Nazi Germany: Ideology, Opportunism, and the Perversion of Justice, edited by Rachlin Robert D. and Steinweis Alan E., 63-87. Berghahn Books, 2013.

Steinweis, Alan E., and Robert D. Rachlin, eds. The Law in Nazi Germany: Ideology, Opportunism, and the Perversion of Justice. Berghahn Books, 2013.

Jasch, Hans-Christian. “Civil Service Lawyers and the Holocaust: The Case of Wilhelm Stuckart.” In The Law in Nazi Germany: Ideology, Opportunism, and the Perversion of Justice, edited by Steinweis Alan E. and Rachlin Robert D., 37-61. Berghahn Books, 2013.

German History in Documents and Images, http://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/index.cfm.

Disbarment: A Jewish Lawyer is Removed from the List of Lawyers Licensed to Practice at the District Court of Tilsit in East Prussia (June 9, 1933). http://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/sub_image.cfm?image_id=1942&language=english

Jarausch, Konrad H. “The Perils of Professionalism: Lawyers, Teachers, and Engineers in Nazi Germany.” German Studies Review 9, no. 1 (1986): 107-37.

Johnson, Eric A. “CRIMINAL JUSTICE, COERCION AND CONSENT IN ‘TOTALITARIAN’ SOCIETY: The Case of National Socialist Germany.” The British Journal of Criminology 51, no. 3 (2011): 599-614.

Koonz, Claudia. The Nazi Conscience. Harvard University Press, 2005.

Johnson, Eric A. “Gender, Race and the Gestapo.” Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung 22, no. 3/4 (83) (1997): 240-53.

DOUGLAS, LAWRENCE. “The Trial by History.” In The Right Wrong Man: John Demjanjuk and the Last Great Nazi War Crimes Trial, 216-46. Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2016.

Ernst Fraenkel, The Dual State: A Contribution to the Theory of Dictatorship Reprint Edition. Oxford University Press, 2018

Johnson, Eric A. “German Women and Nazi Justice: Their Role in the Process from Denunciation to Death.” Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung 20, no. 1 (73) (1995): 33-69

Geerling, Wayne, Gary B. Magee, and Robert Brooks. “Faces of Opposition: Juvenile Resistance, High Treason, and the People’s Court in Nazi Germany.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History44, no. 2 (2013): 209-34.

Rundle, Kristen. “The Impossibility of an Exterminatory Legality: Law and the Holocaust.” The University of Toronto Law Journal59, no. 1 (2009): 65-125.

Number 8 - We Are Here For YOU!!!

Here is How We Are Different – It is in Our Rules!

We will ensure –